Displaying & Interpreting Synagogue Data

This is the second post about my synagogue data project. Here is the first post. I am using 19th and 20th century synagogue records to learn about Jewish life in America. To interpret this data, I used the Matplotlib and Pandas Python package.

Dates of Establishment

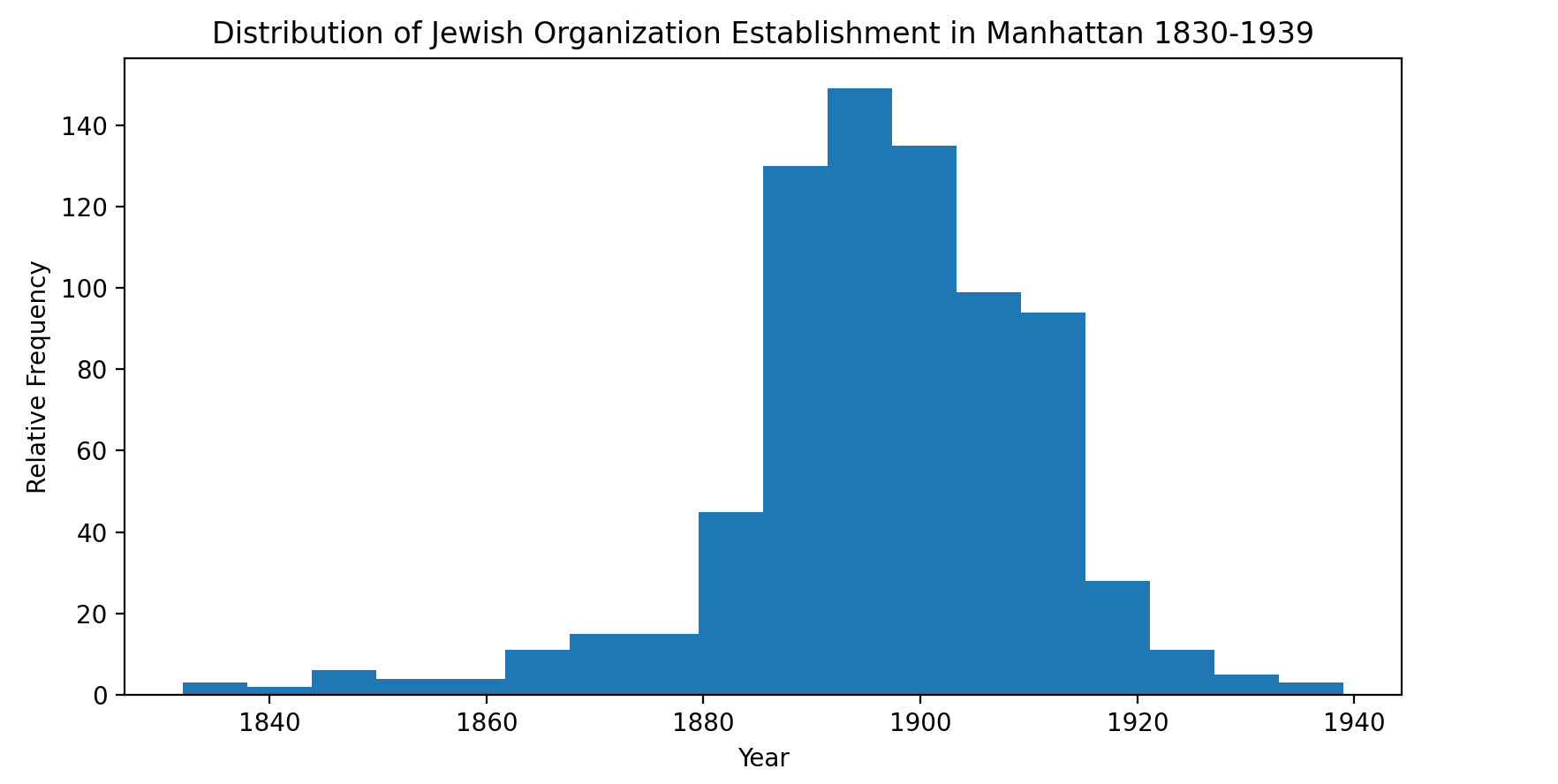

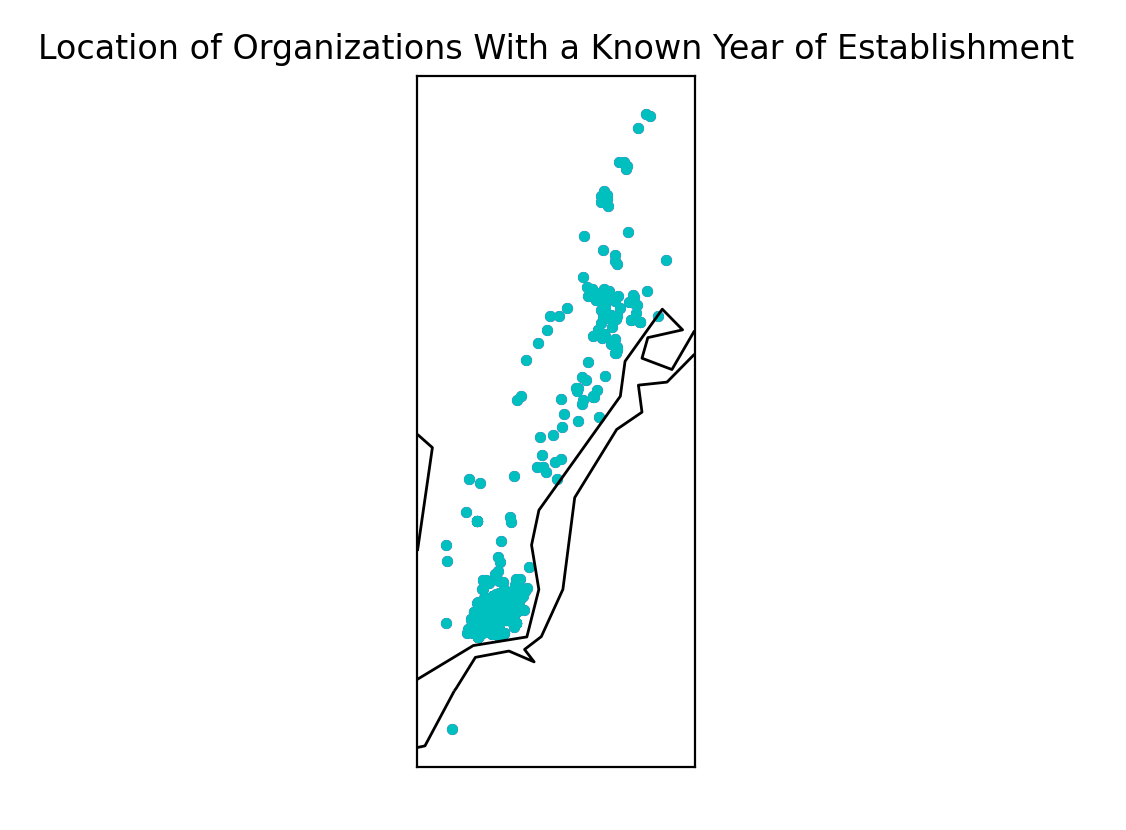

Trimmed for outliers*, the distribution of organization dates looks like Figure 1. This is only for organizations for which the year of establishment is known. Many organizations did not have a recorded year of founding. Of the 1,016 organizations that are in the dataset, the year of organization is known for 762 (see fig. 3). This can be attributed to insufficient record keeping or loss of such records. The mode is in 1892. This is the year when the most organizations were established. The median year of establishment is 1896. Organizations that affiliated themselves with a particular location had the same distribution and median as those that did not have an affiliation.

This is, of course, the data trimmed for outliers. Well, outlier. Congregation Shearith Israel was established in 1654 by Dutch Sephardim.

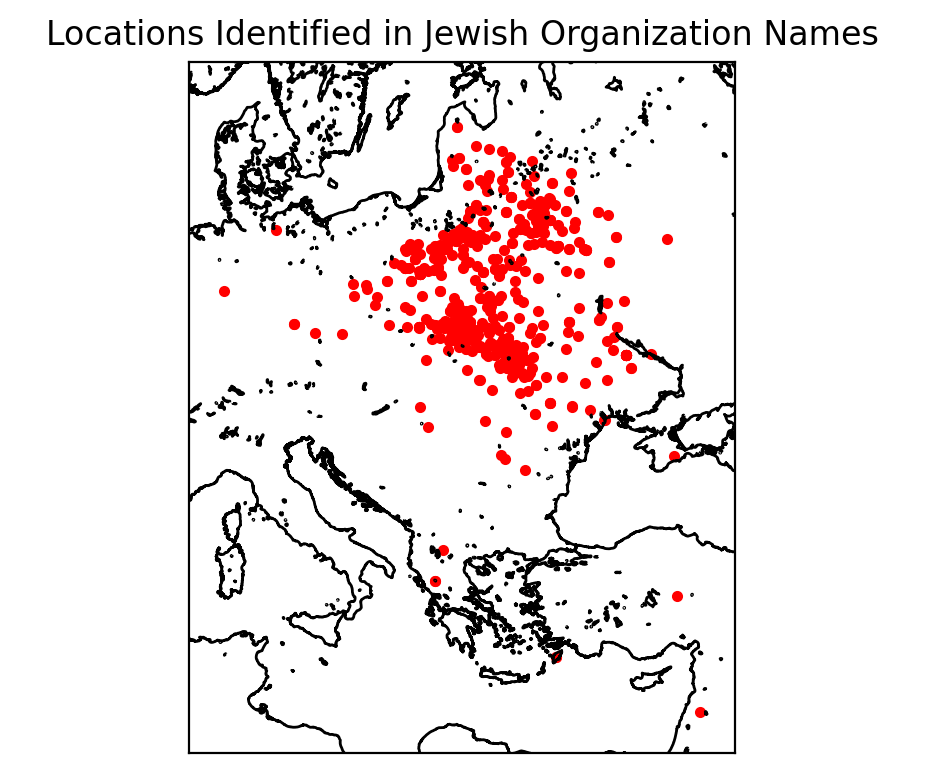

Before 1885, no more than 8 organizations had been established in a year. Suddenly, in 1885, this number rose to 23 in a year. The number of organizations established in a year would not consistently return to single digits until 1917. (In 1908, only 8 organizations were established. However, this year was surrounded by larger numbers on both sides. This may be attributed to one of the primary source book being the 1907-08 Jewish Yearbook. Organizations established in late 1908 may not have made the cut.) The literature on Jewish immigration to New York generally describes it as occurring in three waves, each larger than the last. The first was a small wave of Dutch Sephardic immigrants (like those that established Congregation Shearith Israel). The next, occurring in the mid-nineteenth century was a wave of German Ashkenazi immigrants. In “New York Jews and the Quest for Community,” published in 1922, Arthur Goren claims that in “the eleven years which preceded the outbreak of World War I, over 10,000 Jews arrived annually from Eastern Europe.” Russian Jews moved to New York in large numbers and comrpised a large part of the Lower East Side’s population. (You’ll not that the map in Figure 3 shows few people identified with places in modern Russia. However, many Eastern Europeans from the time are referred to as “Russian” because the Russian Empire did not fall until 1917. As explained in the first article, I noted the current nation where towns are located.)

Locations of Origin

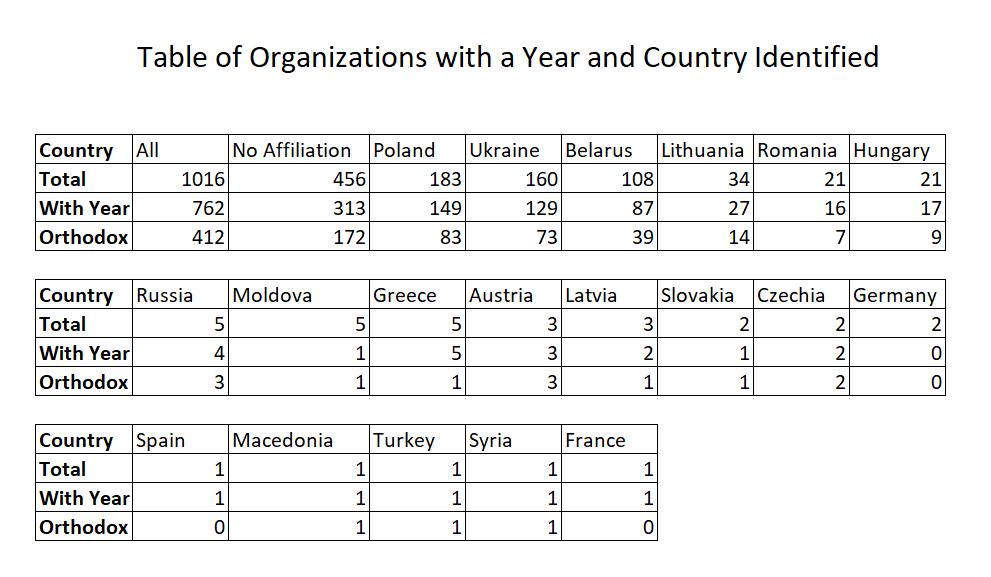

This table presents the nations that that organizations identified with. It also presents the number of organizations with a known year of founding and that identified as Orthodox.

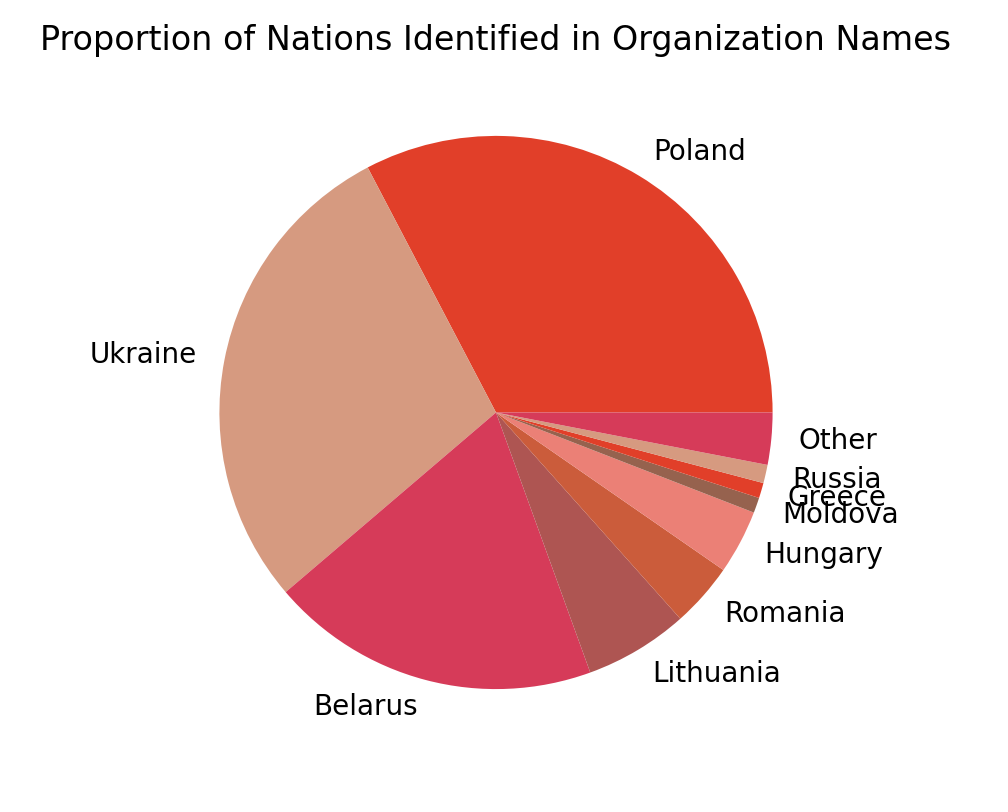

The nations are ordered from most to least frequent. Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus are the three most commonly identified nations. The national identification proportions are shown in figure 3.

The actual towns are mapped in Figure 4. All of the organizations with an identification identified somewhere in Europe.

This map makes it evident that most organizations originated in Eastern Europe, and this makes sense given the number of 20th-century immigrants.

However, an absence here is more striking than a presence.

Figures three and four show that there were only two organizations in all of Manhattan that identify themselves as German.

This contrasts greatly with current assumptions about German-Jewish immigrants.

Where are all the Germans in Manhattan? There are two distinct possibilities.

First, it is possible that Germans did not live in Manhattan. They may set their sights beyond Manhattan and instead preferred other boroughs or suburbs. This may have been eventually true.

However, there is evidence of German Jews living in Manhattan. There was a well-known community of German Jews living in Washington Heights, and German Jews are documented to have lived in the Lower East Side as early as 1848.

This is why I favor a second theory. Organizations were still established in the time that German Jews are purported to be moving to Manhattan. These organizations simply didn’t identify themselves as German. Some may argue that this is because Germany did not exist at the time. This is true. However, when I note that these groups were “not identified as German,” I mean they were not identified with towns or cities now located in the modern state of Germany. Others may argue that later German-Jewish immigrants may have been troubled by rising fascism and antisemitisim in Germany. This is also true. But why didn’t they identify with their towns and cities instead of their nation? And could this not also have been said of those living in the Russian Empire?

I theorize that when Germans came to the United States, they were more prepared to sever the ties from the towns they came from, likely because of the assimilationist Reform Movement’s prominence there. Their lack of location identifiers wasn’t about Germany. It was about America and their determination to make a new life there.

Ideally, I would be able to compare the total amount of German-originated organizations with the fraction that identified themselves as such. Because this dataset is all that remains, this endeavor would be fruitless. One could compare the naming practices of Eastern and Central European groups in order to determine which unnamed organizations fall into which category. However, the sample size for Central European groups is so small that this is impossible. The sample size is small because the Central Europeans did not identify as such, which is what created this question in the first place. To answer these questions about local and national identity, we have to look at how groups organized and located themselves once in the United States.

Locations in New York

Lets look at the geographic progression of establishment. These are only for the organizations for which the year is known, but there is not likely a meaningful difference between organizations for which the year is unknown.

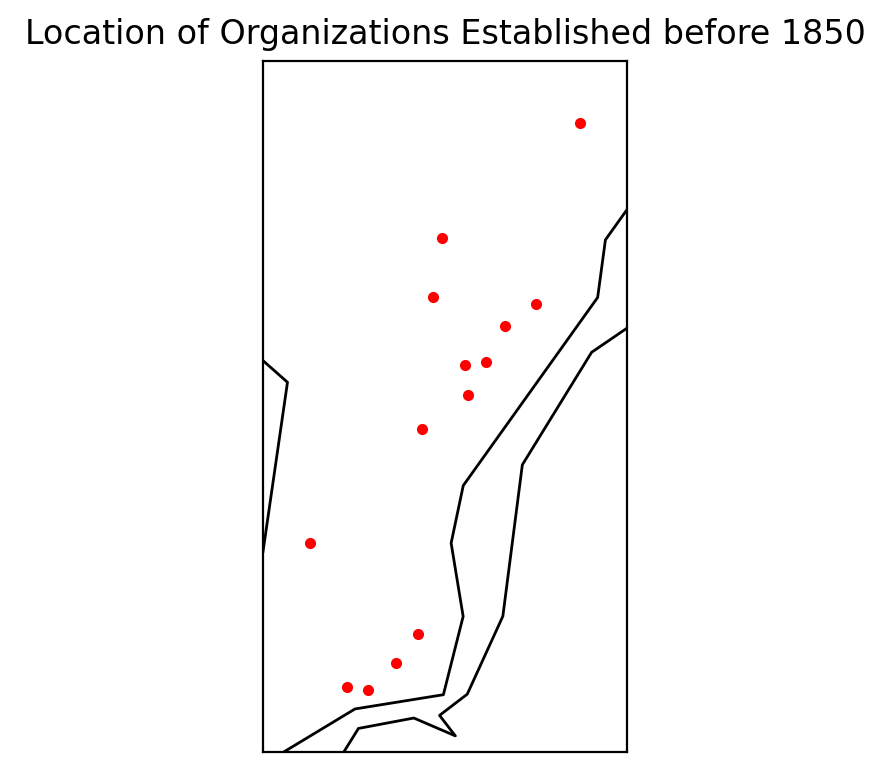

Figure 5 shows the locations of all of the synagogues established before 1850. At this point, the organizations seem to be fairly dispersed around Manhattan. However, there are already two groupings in the Upper and Lower East Sides.

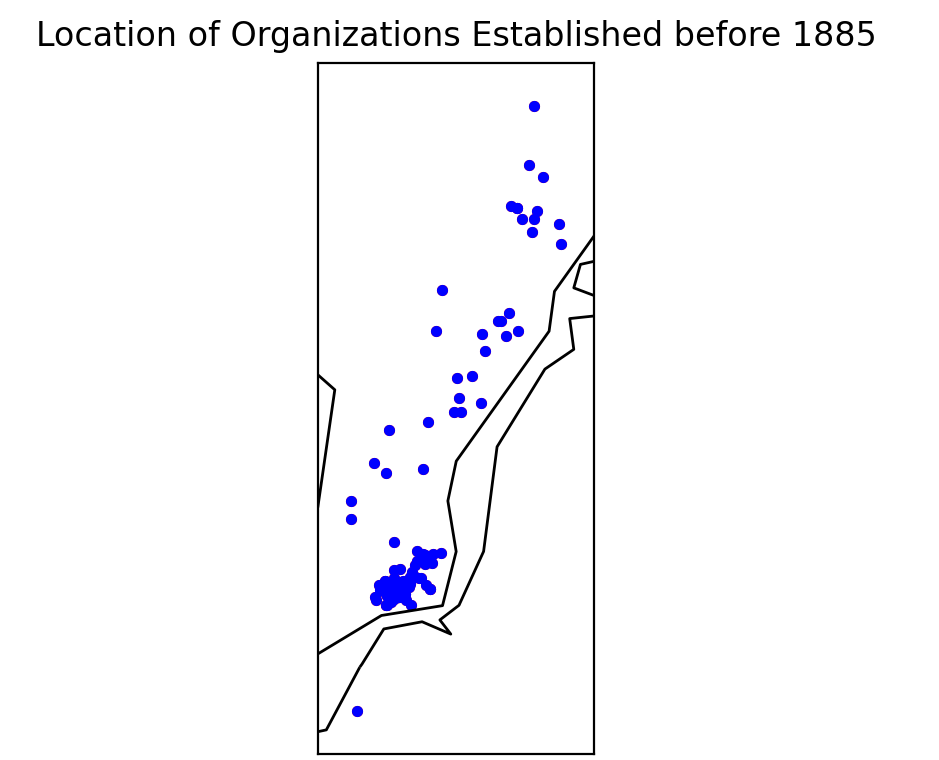

Figure 6 is a snapshot of all organizations established by 1885, including those established before 1850. At this point in time, the largest cluster is in the Lower East side. One organization has been established across the Williamsburg bridge, and there are a few in Harlem.

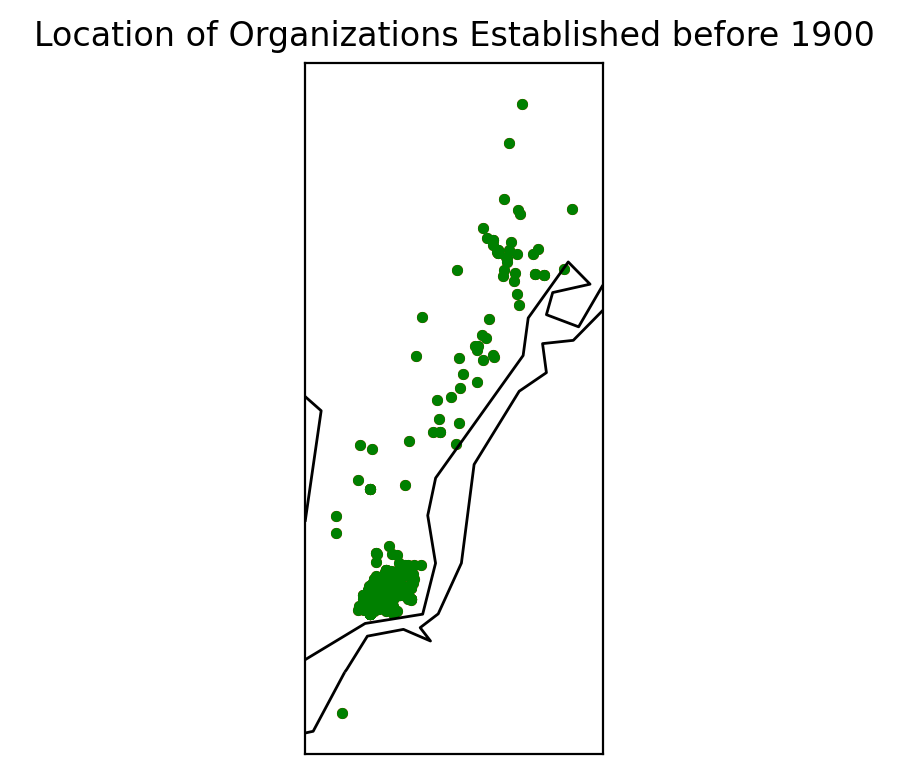

By 1900, there are so many Jewish organizations in the Lower East side that they become difficult to distinguish on a small map (Figure 7). Now, there are organizations as far north as Washington Heights. It is not totally clear whether the geographic scope of the records or of the actual organizations increased.

In the next decade, the Heights, Harlem, and Upper East Side neighborhoods quickly grew. Growth in the Upper East Side could be attributed to the economic success of many Jewish Americans. Conversely, growth in the Heights & Harlem might be attributed to the relocation of factories and industry to this less expensive area. The Lower East Side was also a huge industry hub (especially for textiles). Jewish immigrants were not alone in the Lower East Side. Many immigrants of different ethnic and religious backgrounds lived in this area.

Figure 8 is the map of every synagogue established up until about 1939. The Upper and Lower East sides have the largest clusters. The east side of Manhattan has the majority of all organizations from this time. Note that when organizations were located outside of the east side, they tended to crop up in pairs. This could be because they shared resources. Running a formal synagogue was very expensive because of all the necessary matierals (sefer torah, siddurim, etc.). Therefore, congregations could have shared these items. This sharing presents the second reason for closeness: orthodoxy. Orthodox Jews may not carry things between different domains or use electricity on Shabbos (the sabbath), so congregants must live close to one another and their place of worship. A higher concentration of Orthodox Jews among these smaller communities would explain these split-off neighborhoods. It could be that organizations only rented in less expensive areas, so the price was a draw for both groups.

I hypothesized that these pairings could be based upon country of origin. While some countries dominate the proportions (Figure 3), maybe Jews from countries that did not have existing social support in the United States established their synagogues and organizations away from the main Jewish structure. Polish, Ukranian, and Belarussian Jews had large support systems because they had many peers that spoke the same language or dialect. Other, smaller groups may not have had this social infrastructure. Polish immigrants would have moved close to the Polish support center (Figure 9). But, say, Greek immigrants wouldn’t have gotten the same support in those Polish areas. Therefore, it made no difference to them where they lived.

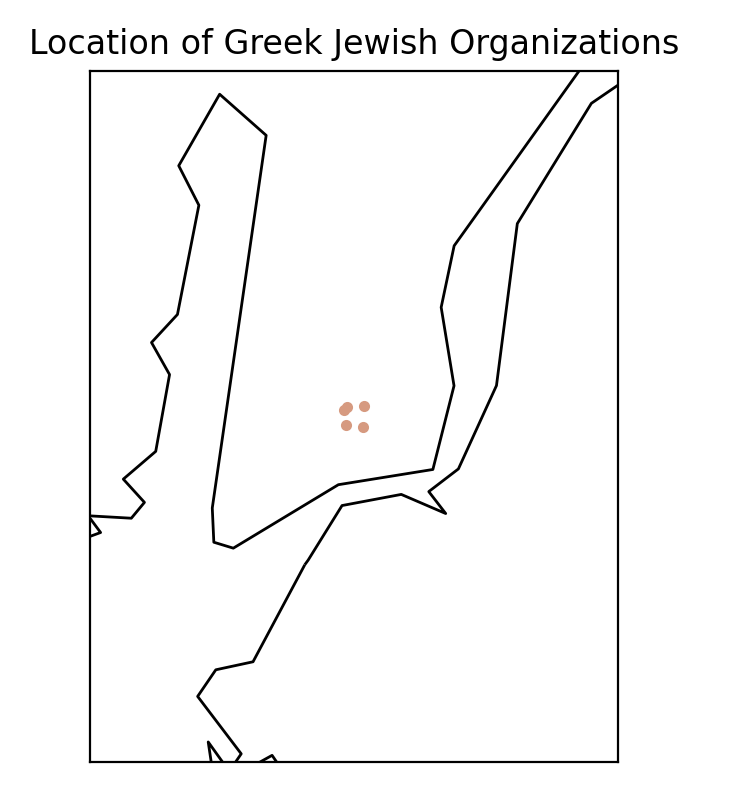

This generalization isn’t necessarily supported by Figure 10. Greek-Jewish immigrants did live close together, but not necessarily far from everyone else.

This generalization isn’t necessarily supported by Figure 10. Greek-Jewish immigrants did live close together, but not necessarily far from everyone else.

There are other problems with these generalizations. First, the language barrier was not as insurmountable as you might think. Many Eastern European/Russian Jewish immigrants spoke Yiddish. Though there were (and still are today) dialect rivalries, many Jewish immigrants could speak to one another. Compared to Americans and other immigrants, Jewish immigrants had much more in common with one another. (There are several exceptions to this rule, namely that many Sephardim did not speak Yiddish but Ladino or another language common in their place of origin.)

The second problem with this belief is that many of these nations did not exist. The Russian empire was still strong, and modern borders had not been settled. It is therefore unlikely that these immigrants had some kind of cohesive national identity. This is an anarchronistic interpretation. Lastly, even if these nations did exist in their modern forms, it is unlikely that ostracized Jewish immigrants would align with them in any capacity.

So, there was no nationalism. Then how did people group?

The answer might be in their localities.

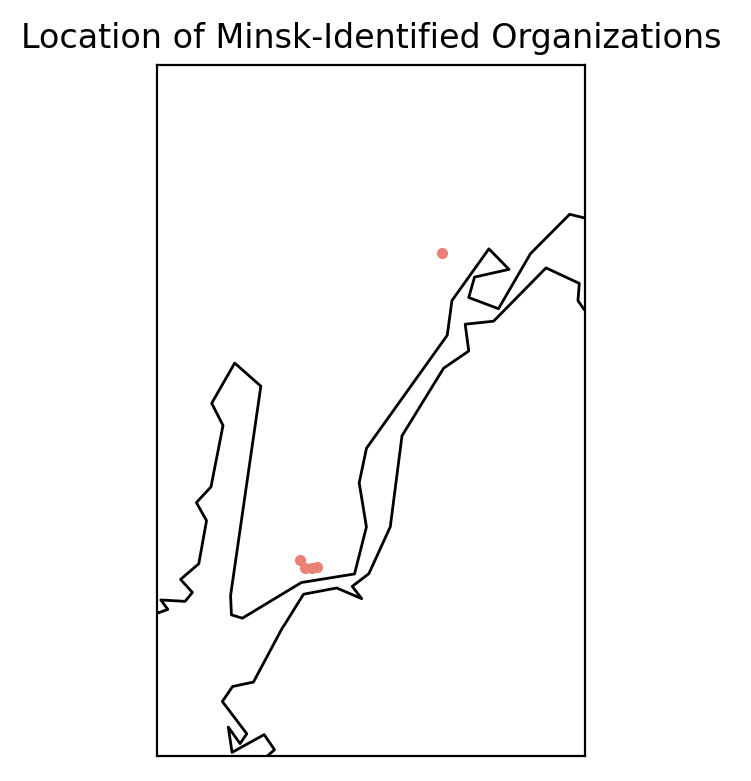

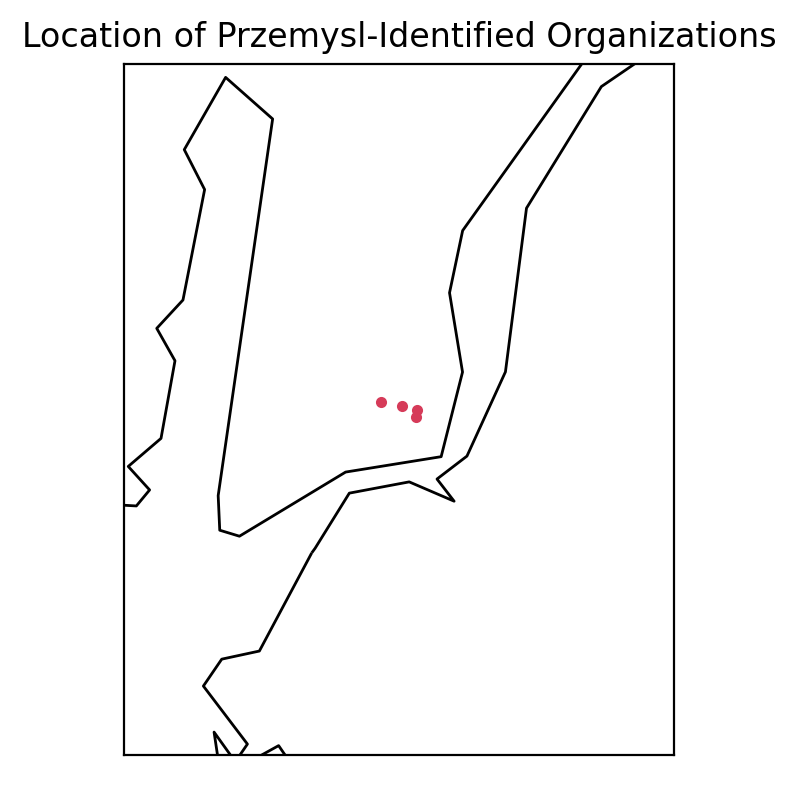

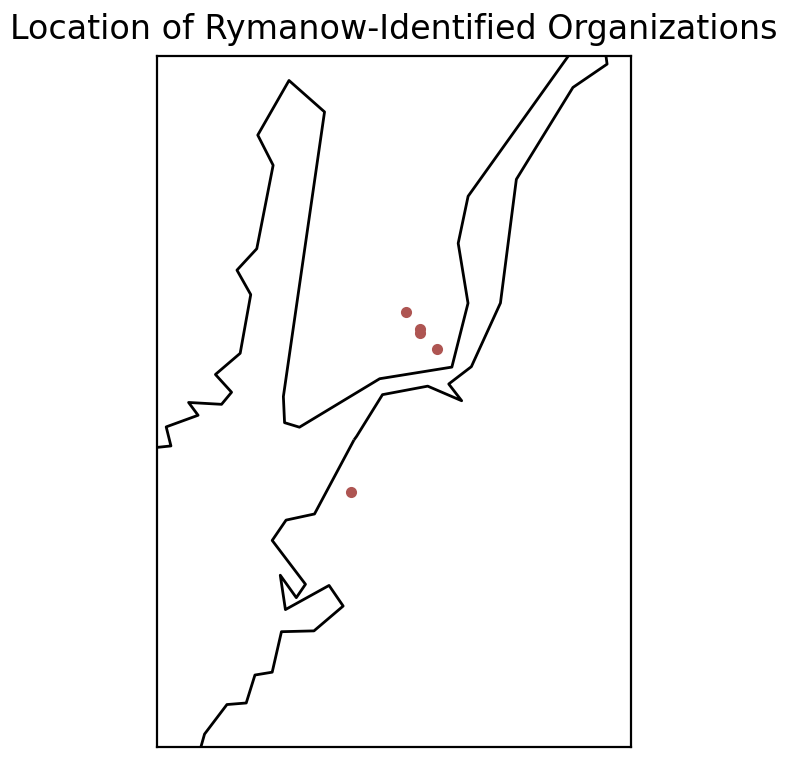

Look at the locations of these Minsk-identified organizations. They are (save an Upper East Side outlier) close together. We see this again with Przemysl, Poland (Figure 12) and Rymanow, Poland (Figure 13).

These are the only towns with enough organizations (4+) to look at their grouping patterns. But we can see that people that identified with one city or town remained close together. This seems very natural. Immigrating to a new country is difficult, so familiar accents, practices, and faces can be a great comfort.

But in this local-identification, we find the answer to our earlier question.

Why didn’t German Jews identify with Germany?

We’ve already established that there was no modern Germany and that German Jews didn’t even identify with their towns. We have also discussed the Reform movement’s value of assimilation.

But the Reform movement is much more than this. Unlike Orthodoxy, the Reform movement’s observance does not limit the carrying of objects of Shabbos. Observers can also use electricity and transportation on holy days. This decreases the need for tightly packed Jewish communities.

Just before the war, nearly 60% of German Jews lived in “urban areas with more than 100,000 inhabitants.”

Unlike Russian Jews, many Germans lived in cities. By the mid-nineteenth century (when most German Jewish immigrants came to the United States), “cultural isolation was almost completely gone.” Liberalizing forces granted German Jews social and geographic mobility. These forces, however, were exclusive to Western Europe.

Meanwhile, many Polish and Russian Jews lived in small towns. If they lived in cities, they likely lived in a Jewish quarter or neighborhood.

What does this mean for New York neighborhoods? It means that German Jews didn’t establish German Jewish communities because there were not as many communities to translate. There were, of course, synagogues. However, religion was just religion. There was no drive to live near fellow congregants because they did not necessarily provide the comforts of home.

It appears that the more assimilated you are, the less you care about the nation.

Conclusions

Economic mobility and assimilation into Protestant society decreased German Jews affiliations with their hometowns. This is not a new idea. In the past, many people lived in towns where their families had been for generations. In the industrialized world, this is no longer possible. How many of us have severed ties with homelands because of economic conditions? But Russian Jews, who had been dependent on the safety of tight-knit neighborhoods, mirrored their old conditions in a new land. These organizations are a strong proxy for immigration trends. However, there are some limitations. Obviously, we can only know what was recorded in the records. The Jewish Year Books are not infalliable. Additionally, it’s not clear what “organization” means to the record keepers. It’s possible (though extremely unlikely) that there were not more Russian immigrants. Perhaps they just created smaller organizations. However, as the data is, it accurately reflects the rate of Jewish immigration to the United States.